The Philippines has slipped again.

In 2025, the country dropped six places in the global Corruption Perceptions Index, landing at 120th out of 182 countries. It’s a ranking that stings—and one that reflects a growing public anger, especially after the flood control projects controversy exploded into one of the biggest corruption scandals in recent years.

The index is released by Transparency International, a global watchdog that tracks how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be. The assessment is based on the views of experts and business leaders—people who see how power is used, and abused, up close.

And what they see in the Philippines is troubling.

Corruption, as measured by the index, takes many forms.

Bribery that quietly changes decisions.

Public funds diverted from their purpose.

Officials using public office for private gain—with little fear of consequences.

It also looks at deeper, systemic problems.

Weak efforts to control corruption.

Endless red tape that opens doors for abuse.

Nepotism in government appointments.

Poor transparency around officials’ finances.

Limited protection for whistleblowers.

Power captured by a few, at the expense of many.

And restricted access to information the public has a right to know.

All of these factors are weighed using data from 13 independent rating agencies, covering 182 countries. Scores range from 0, meaning very corrupt, to 100, meaning very clean.

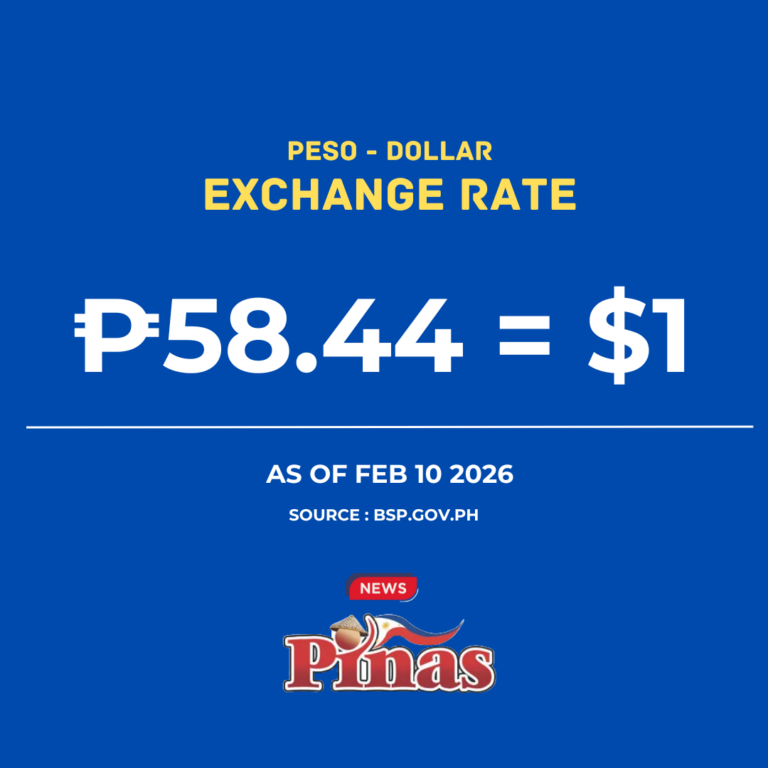

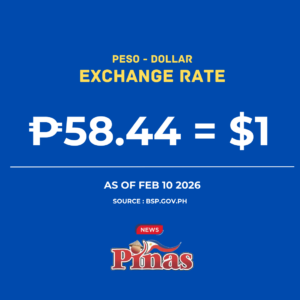

The Philippines scored 32.

That’s well below the global average of 42—and worse than last year’s score of 33, when the country ranked 114th. One point may seem small. But in this index, it was enough to push the Philippines further down the list.

Within Southeast Asia, the picture is even more sobering.

The Philippines now trails behind Singapore, which ranks near the top at 3rd, as well as Malaysia, Brunei, Timor-Leste, Vietnam, Laos, Indonesia, and Thailand. Only Cambodia and Myanmar, currently under military rule, ranked lower.

At the other end of the global scale sits Denmark, the world’s cleanest government by perception. At the very bottom—locked together in last place—are Somalia and South Sudan.

For the Philippines, the message is clear.

This isn’t just about numbers or rankings.

It’s about trust.

It’s about accountability.

And it’s about how long the public is expected to pay the price for corruption that never seems to end.